Drenching unnecessarily costs a lot in labour and drench costs and helps to select worms for drench resistance.

Gone are the days when farmers can afford to drench without testing first. It's concerning that there are no new drench groups coming onto the market, and that the programme to develop a vaccine appears to be stalled. It is vital that we conserve the life of the present drench groups for as long as possible.

Some important points to help in the control of worms.

- Drenching correctly helps to kill worms in the gut and to minimise pasture contamination by worm eggs. Animals should all be given the recommended strategic drenches AFTER monitoring their worm egg count.

- Good grazing management aims to ensure that the most susceptible stock - lambs, kids and weaners - do not graze paddocks containing high numbers of worm larvae.

- Frequently running tests on dung samples determines whether drenches should be given by first finding out the faecal worm egg count.

FEC

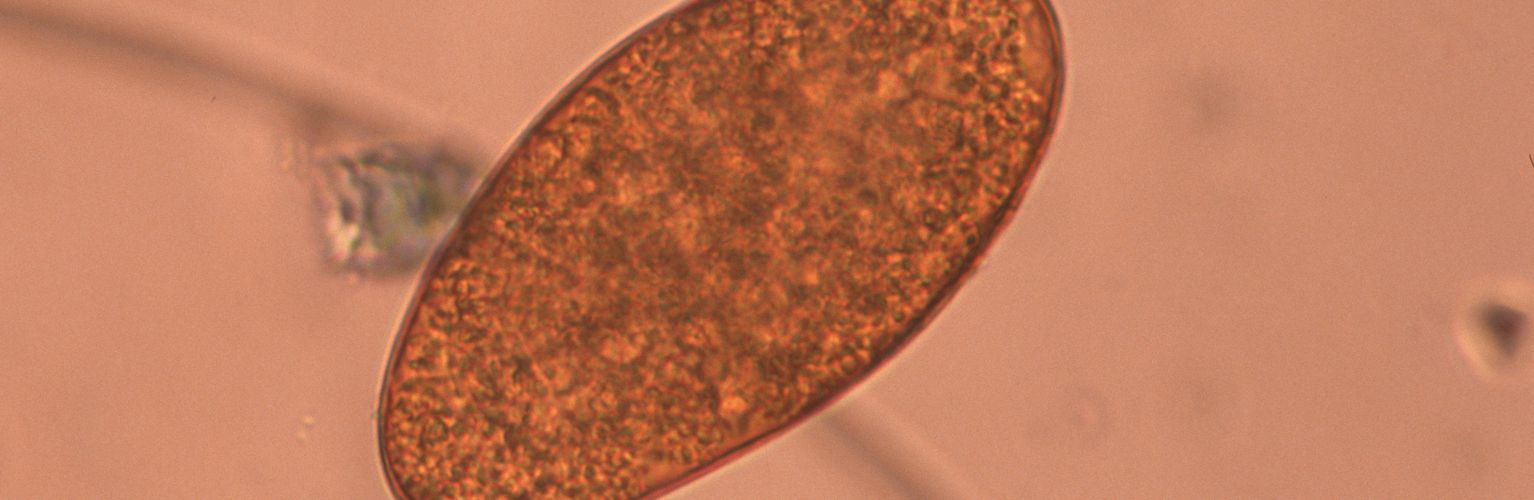

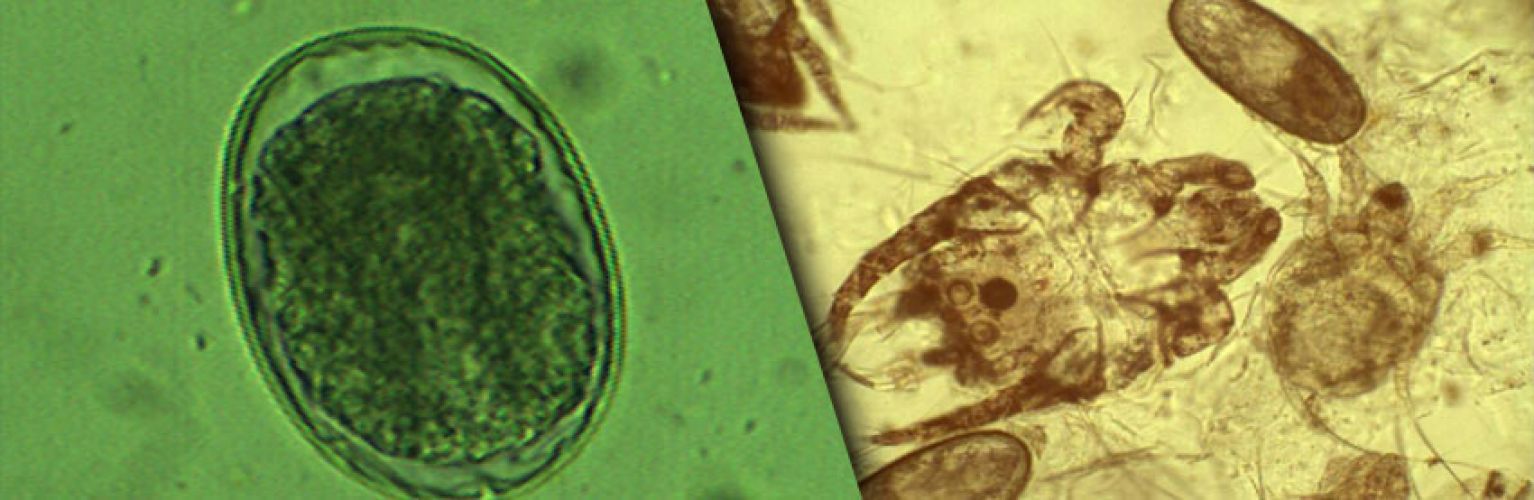

Faecal egg counting (FEC) is the process of determining the number of worms eggs in the faeces of animals. Knowing the FEC can be useful in several ways. A WORM-CHECK test determines the average FEC of 10 fresh dung samples from a mob of animals. This worm egg count is then used as a guide to indicate the severity of a worm infection in the mob and the level of pasture contamination by worms that is occurring while the mob grazes that paddock.

Worms in sheep, cattle and goats can cause major losses. These include deaths of animals, weight loss or reduced liveweight gain, reduced quantity of meat or fibre and reduced milk production. Heavy worm burdens also contribute to depressed appetite and poor feed utilisation, a predisposition to other diseases, plus extra costs for drenches, labour and associated management practices.

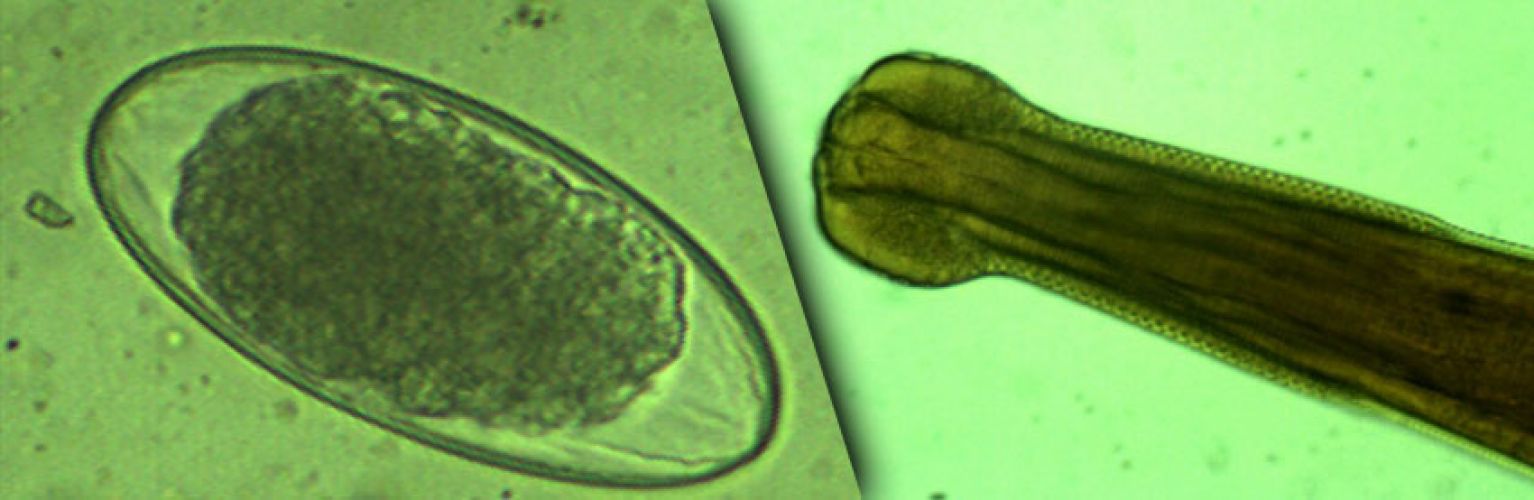

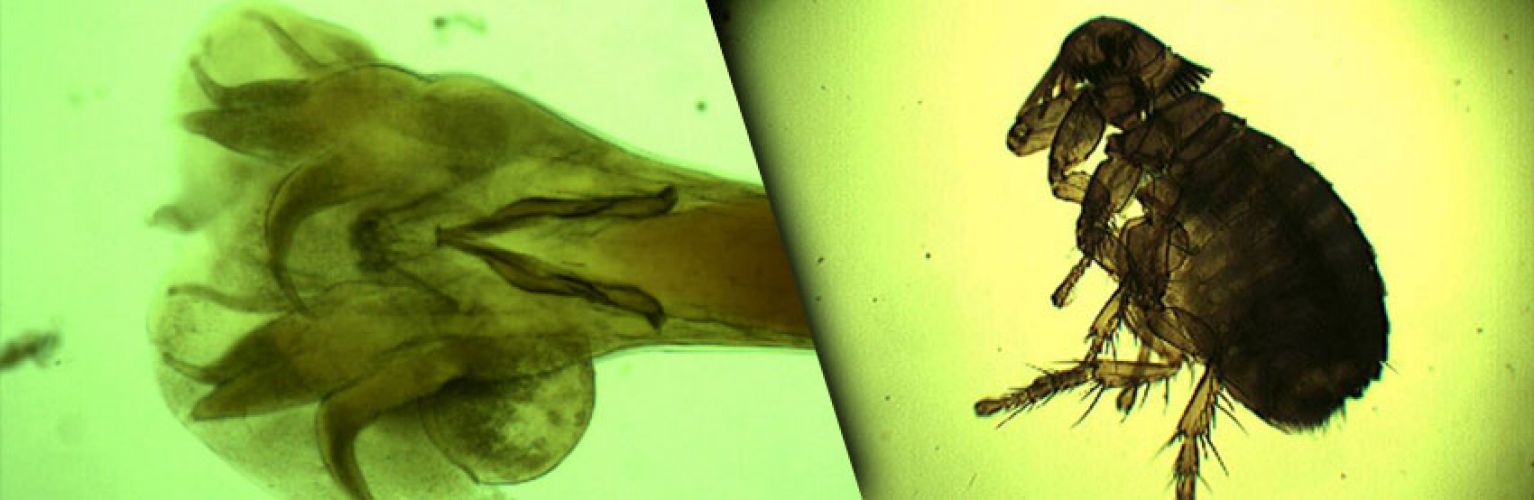

The most important roundworm parasites of sheep and goats are:

- Black Scour Worm (Trichostrongylus spp.), which prefers to live in the small intestine.

- Brown Stomach Worm, (Ostertagia spp.), located in the stomach.

- Barber's Pole Worms, (Haemonchus contortus), found in the stomach, in warmer, moist conditions.

- Thin-Necked Intestinal Worm, (Nematodirus spp.), an intestinal worm that is not very pathogenic. It often parasitizes young animals and is usually the first species of worm to appear when an infestation starts.

Many farmers have unwittingly introduced Barber's Pole worm onto their properties because they failed to quarantine drench newly-purchased animals with an avermectin / milbemycin (Mectin) drench and a mixture of White (BZ) and Clear (LEV) drenches. It's impossible to know the truth of the drench resistance, or Barber's Pole worm, status of the vendor's property. Also, with the rapidly increasing incidence of worms that are becoming resistant to drenches it is vital not to import resistance problems from other farms.

The most important parasite in cattle in temperate Australia is the Small Brown Stomach worm (Ostertagia spp.) Other worms of cattle include the Stomach Hair and Black Scour worms, (Trichostrongylus spp.), the Small Intestinal worms, (Cooperia spp.) and Barber's Pole worm, (Haemonchus placei).

Trichostrongylus and Cooperia tend to produce most damage when Ostertagia worms are also present.

Cooperia affect cattle that are less than one year old and are a particular problem in early-weaned calves. Surveys suggest that the prevalence of Cooperia has increased, but it has not necessarily become a bigger problem. Trials in New Zealand have reported that Cooperia is resistant to oxfendazole, a white benzimidazole (BZ) drench, and to ivermectin, a macrocyclic lactone (ML) drench.