NOTE: If exporting livestock to Western Australia please refer to the special condition on the Liver Fluke - WA tab.

Liver Fluke (Fasciola hepatica) parasites can be a significant threat to the health of cattle, sheep and goats.

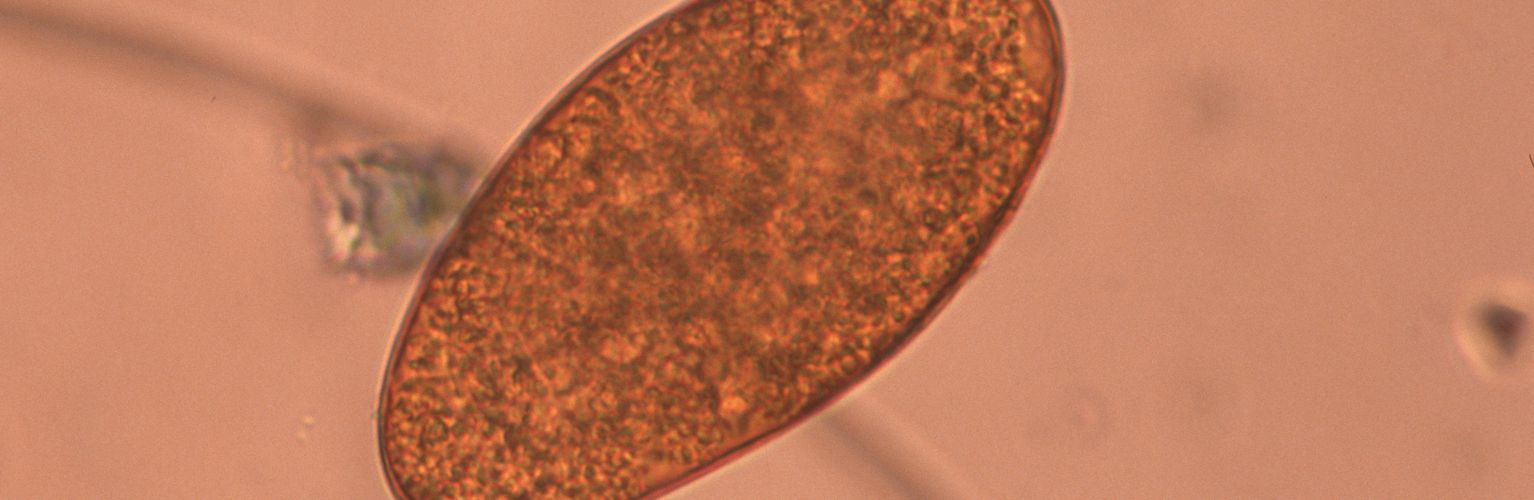

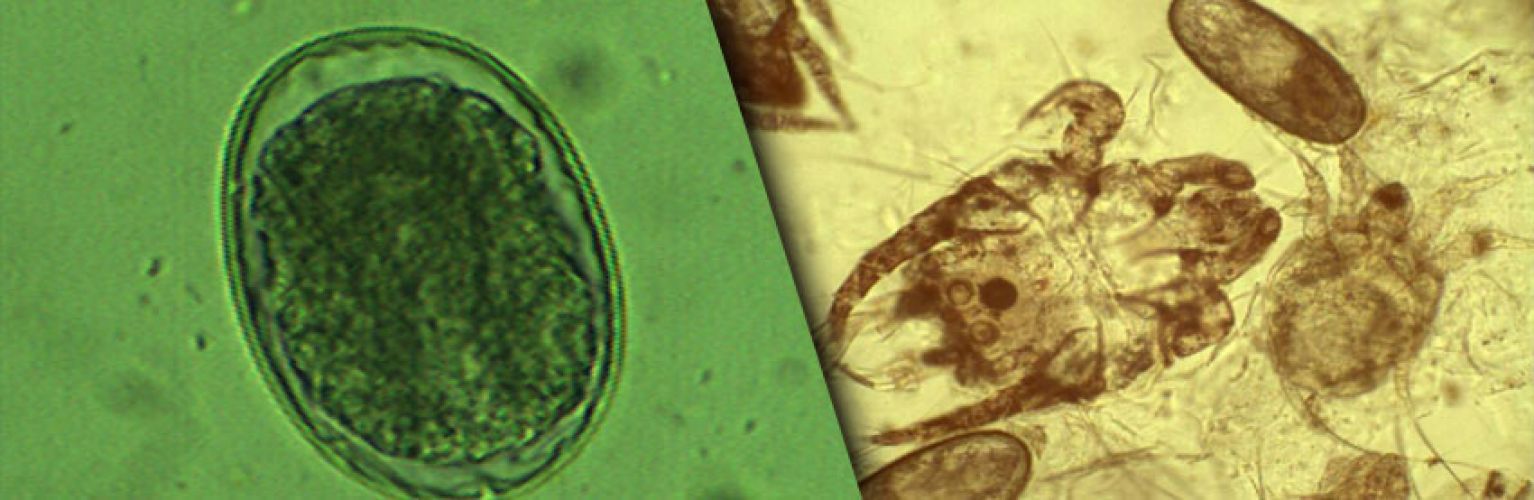

In the laboratory mature fluke can easily be detected by examining faeces for eggs. For cattle we can also test blood and milk, using an ELISA assay.

The presence of eggs (regardless of number) means the animals should be treated - as many immature flukes could also be present.

Immature Liver fluke can be detected with blood tests which measure liver function.

Five to ten animals should be blood sampled by your vet or animal health adviser.

A test can detects the presence of chemical signals given out by fluke in the milk of cows.

Sheep do not develop immunity to Liver fluke while Goats may develop immunity. Cattle do develop immunity.

Moderate to heavy burdens of mature fluke cause a wasting condition, reduced milk production, inferior fleece and poor lamb growth (up to 40% reduction). Heavy burdens of immature fluke cause massive liver damage, haemorrhage and death. Sudden death due to Black Disease may also occur when the liver is damaged by fluke.

Adult fluke can live for up to 10 years in the bile ducts of a sheep's liver, and may produce large numbers of eggs each day. In cattle, liver fluke only live for about a year. Eggs passed in the dung, hatch into microscopic tadpole-type larvae, which wriggle through the film of water on the grass. They hunt for a particular small water snail - Lymnaea, and burrow into its body.

Further development occurs inside the snail and one larva may multiply into about 400 infective swimmer stage parasites. These work their way close to the outside in the head region of the snail. When the snail starts to emerge from the water, the infective stage larvae break out of the host's body. They swim to the edge of the water and attach themselves to grass stalks. They develop a tough outer coating which can resist dehydration, and are then known as cysts. Stock on irrigation or a "green pick" alongside water, particularly in late summer and autumn, then eat these infective cysts of fluke.

Once inside the animal, these parasites burrow through the gut wall and move to the liver. During the following 6 weeks they move about in the liver causing considerable damage to it. After entering the bile ducts, the fluke mature in another 6 weeks and produce eggs. Major losses can occur because liver fluke have an enormous capacity to multiply when seasonal conditions are favourable.

In fluke-prone areas a fluke drench is given to sheep and young cattle in July/August, irrespective of seasonal conditions, to kill egg laying adults. This will reduce infection levels in snails in spring. A further treatment in February may also be warranted for stock grazing on flukey country or irrigated pastures. Sheep on irrigated summer pastures could also require further treatment in April/May.

Methods for snail control are limited. Paddock layout and irrigation water management are important factors in reducing snail numbers. Fencing of wet areas will also aid control. Chemical treatments, such as spreading Copper sulphate, (Bluestone) to eradicate snails are not successful. There is also the risk that the chemical will wash into dams and streams, altering the natural balance of the water and possibly becoming the starting point for all sorts of other problems with water quality. Attempting to eradicate snails by chemical means are therefore definitely not recommended.

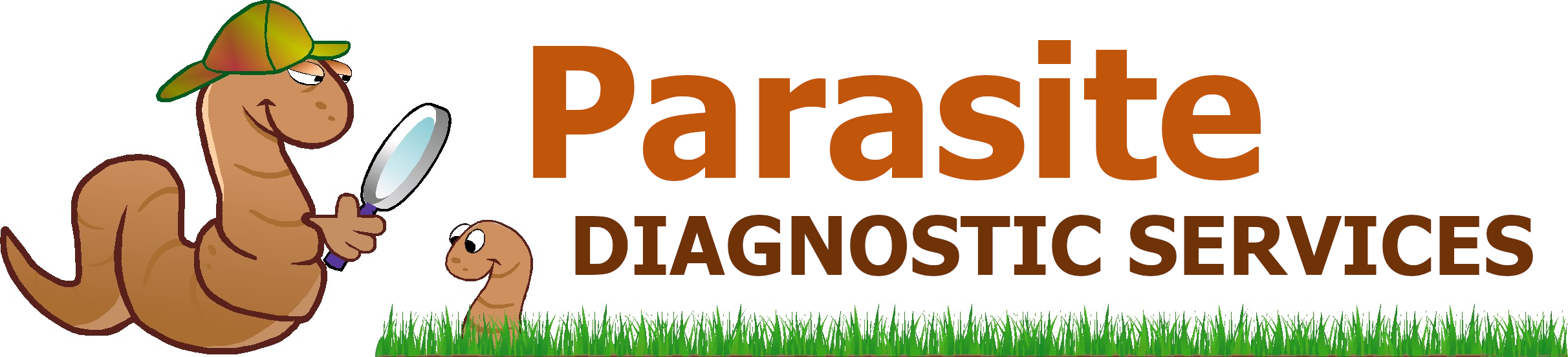

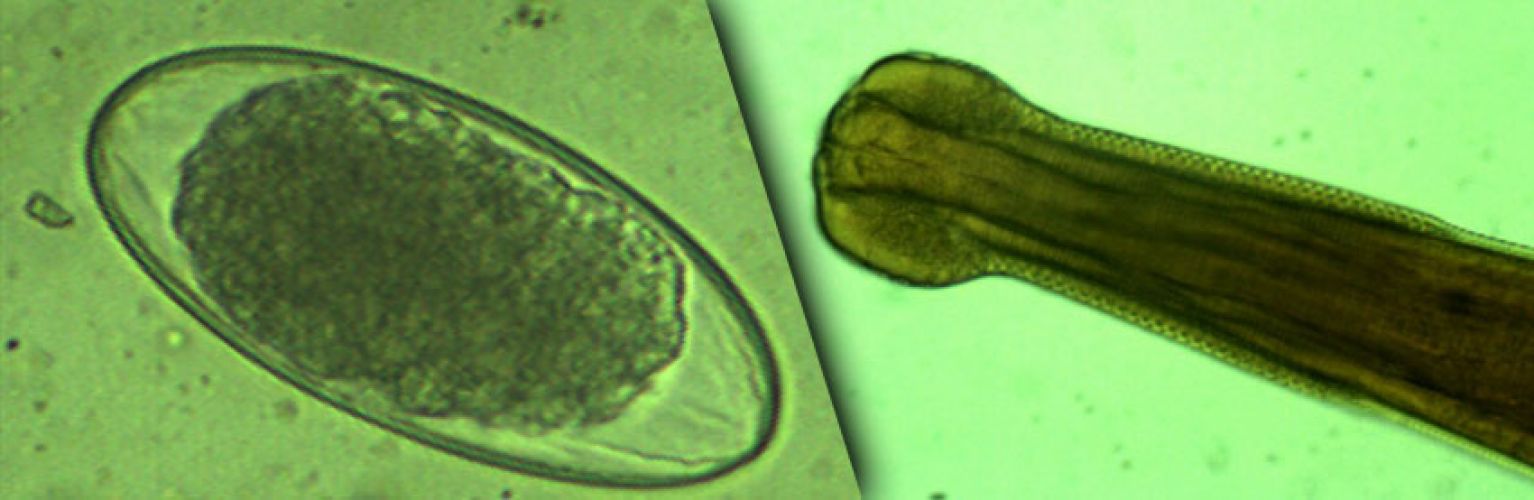

There have been quite a lot of cases of chronic Stomach Fluke (Paramphistomes), seen in cattle recently, especially on irrigated or very wet paddocks. This is an entirely different beast from a Liver fluke. They are inverted pear-shaped flukes that are found in the rumen of cattle and sheep. Normally they are not thought to be very harmful if present in low numbers. However, heavy infestations can cause scouring, weakness and losses in animals. Some of our clients have recently thought that their Liver fluke drench has not been working as cattle have still been scouring despite treatment. A laboratory test in most of these cases revealed the presence of Stomach Fluke eggs. These are easily recognized under the microscope, as they are markedly different in appearance to Liver Fluke eggs.

©

2026

Parasite Diagnostic Services ABN: 83 359 351 104